Ladies and gentlemen. Let me introduce the newest member of the Northern Rail family.

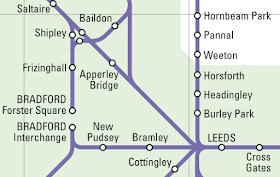

Yes, they've updated the Northern Rail map, and yes, Apperley Bridge has finally made its debut. I didn't think they'd bother, to be honest, but it's nice to see it has arrived. I would've thought they'd have added Kirkstall Forge next door to save having to update the map later - perhaps with an asterisked Opening Spring 2016 - but apparently not. (What's taking them so long, by the way? I mean, once you've stuck a couple of platforms down, surely the station is open - the waiting rooms and car park and all the rest are just gravy you can finish later.)

Incidentally, in 2014 I had a stab at what I thought the new bit of map would look like. Unfortunately I worked on the assumption that all the trains on that stretch of line would stop at the new stations, but otherwise, not bad.

So I've updated my spreadsheet. There are now 534 stations on the Northern Rail map, leaving me with 10 to collect (the 15 I had on January 1st, minus Woodlesford, Outwood, Clitheroe, Whalley, Langho and Rampsgreave & Wilpshire, but plus Apperley Bridge). And no, I won't tell you which ones they are.

P.S. There's one other tiny change - the Todmorden Curve is now on the map. However, I think that might have been there a while and I just forgot to mention it.

Tuesday, 26 January 2016

Monday, 25 January 2016

Irrational Thoughts

Have you ever developed an irrational hatred for something? A completely unfounded, based on absolutely nothing, dislike for a person, or a tv programme, or a food? You've not sampled it, you've heard good things about it, but you just can't get on board.

That was me and the Clitheroe line. I just didn't want to go there. I had absolutely no reasoning behind this. It was just, over the years, I developed a strange antipathy towards a part of the Northern Rail map without ever understanding why. I just didn't want to go there.

I had to in the end, of course, so I finally slogged my way up to the far reaches of Lancashire. And it was a slog - train to Liverpool, train to Preston, train to Blackburn. Finally I got off at Ramsgreave & Wilpshire and took a look round.

Nothing out of the ordinary. Nothing that different. My dislike seemed unjustified for the moment. I climbed up to the street level and, after a pause to let some burly workmen by in case they laughed at me, I took my sign picture.

The curious part of Ramsgreave & Wilpshire - besides its clunky name - is it's a relatively new station, only opened in 1994. Passenger services north of Blackburn were closed by Beeching in the sixties, a decision which was, as usual, astonishingly short-sighted and stupid. Freight services continued though, making it relatively easy to reopen the line as far as Clitheroe under the John Major government. The original station site had been built on, so a new one was slotted in under a road bridge.

I wandered down to the main road, passing the Bull's Head pub with an actual stone bull's head over the door, and quickly crossed a local government border. It was marked with a variety of signs - too many signs, in fact (I couldn't fit in the one warning they had zero tolerance for dog poo). Your Council Tax money at work there.

The road was a moment of level space on a hillside; to my left, the road plummeted downwards, while to my right, it staggered up. New houses were being squeezed into gaps between classy Victorian semis, pocket homes inches from their neighbours but still advertised as "luxury" or "executive" or "architect-designed". Newsflash, home buyers: all houses are architect-designed. They have to be, or the roof will fall off and you'll have a drainpipe in your front room.

A bus stop advertised its location as "Wilpshire Old Railway Station" and, peering through the trees, I could see the moss-covered remains of a platform by the side of the tracks. The new station seemed to be far better located, in the actual heart of the village and off the main road.

A dart across a dizzyingly unsafe crossing and I was climbing the hill further. The snow of the previous weekend was almost all gone; it had left behind "icy road" warning signs and the occasional grubby heap where it had been shovelled off a driveway and become compacted. There were Christmas trees in the front yards, waiting to be picked up by the bin men, still looking surprisingly green. I decided that they'd been sprayed with something to stop them dropping on your carpet, and these were all undead pine needles, trapped on the branches forever long after they'd died.

Past Somerset Avenue, a private road with "No Turning" underneath the sign in a bold font - what is the problem with people turning round in your road, really? - I encountered a house called "Moonrakers". Obviously I'm assuming that the owners are huge Bond fans, and not just people from Wiltshire. The headquarters of Child Action North West, a stout Victorian building made of grey stone, were marked as Orphanage on my Ordnance Survey map, and despite the yellow and red signage, it still carried the gloom of a children's home. After that it was countryside, green grass beneath grey skies, hillsides dotted with still wind turbines.

It was just temporary, a breathing space between villages, and soon Langho's suburban quiet was wrapping itself round me. Neat roads with houses discreetly tucked behind hedges. I was forced into the road by an old couple who were holding hands and absolutely refused to give up an inch of the pavement to me, the bastards. Obviously I clubbed them to death immediately afterwards. In my head.

It was a little bit odd, Langho, and not just because it sounds like they could only afford half a village name. Something a bit weird. Not just pensioners elbowing me into the path of oncoming vehicles, but also a post office in the middle of a bungalow, a Pontiac Trans Am with flames painted on the bonnet and BAD in its numberplate, a pub with indecipherable opening hours. Just a bit off somehow.

The oddness extended to the station, tucked away down a badly paved side street and still triumphant about the reopening of the Clitheroe Line, twenty two years after it actually happened.

The platforms were splayed, one on either side of a low narrow underpass, and the teenage girl who'd been shadowing me all the way through the village went to the southbound platform. I went through the underpass, then nipped over a stile into an adjacent field so I could pee behind some bushes. It was only when I'd zipped up and turned around I realised that she'd had a fantastic view of me urinating from that platform. I sheepishly trudged up to the northbound side, hoping that the phone call she was making wasn't to the police.

I was a bit early for my train, about ten minutes, so I wandered up and down to keep my circulation flowing. There was an Attractive Local Feature board there, informing me that I was in Jessica Lofthouse Country, plus one of the advertising boards was given over to a mini biography. (I should say that whoever wrote the biography needs to employ a proof reader; it was littered with typos, including a "Jesica" and a "Backburn"). Apparently, Ms Lofthouse was a writer who loved this part of the world and wrote books about the Lancashire countryside and its folk traditions. I'm sure she wrote some wonderful prose, and has a lot of fans, but can you really have "Jessica Lofthouse Country" when she doesn't even have her own Wikipedia page? It's not really Bronte country.

If I'm honest, I took against Jess thanks to that biography. It said that she left money in her will for benches to be erected round Langho, on the proviso that none of them had backs so that people would "sit up straight and admire the view". That's a little bit of a dick move.

The next stage of the trip took me over the Whalley Viaduct, a 48 span, Grade II listed piece of magnificent engineering. As always with viaducts, however, the best place to see them is from the valley below; I didn't even realise I'd travelled over it until I read about it afterwards.

Whalley station is similar to its brothers further down the line, but has a slight advantage in that the old buildings are still there. They're not being used for railway purposes, of course, but it's good to know they're around. It adds to the character of the station.

That big, elaborate gateway to the station should have given me a hint that Whalley considered itself a cut above. As it was, I continued into the centre, thinking it was just a standard Lancashire village. Little houses, an old people's home, a war memorial.

I was starting to get hungry. I'd packed a salad for lunch, part of my latest undoubtedly doomed attempt to be more healthy, but you can't eat a salad while you're walking. It's a two handed, sit down meal. I'd not eaten for about six hours by that point, and my stomach was complaining. I wondered if there was a Greggs in Whalley, so I could have a pastie. (Told you my healthy living aspirations were doomed).

Whalley does not have a Greggs. It would never lower itself to having a Greggs. It turns out Whalley was posh. Properly, glamorously, expensively posh. Its busy, thriving high street was dotted with cafes and restaurants and pubs; there were two dentist surgeries, and a number of beauticians and hairdressers. I could have bought an expensive handbag, or some hand-crafted jewellery, or some superb wines from the Whalley Wine Shop, but a lump of gristle wrapped in pastry? Not a chance.

I went into a delicatessen, ignoring the stares of the men gathered in the window drinking lattes (my sweaty forehead and my walking trousers and my general air of poverty immediately marked me as an outsider), in the hope they might have something. There was a lot of artisan cheeses and meats, but the only crisps you could buy were huge bags of Tyrell's, with their fancy flavours, and the chocolate bars were slabs of high cocoa content organic fair trade nonsense. There was no-one behind the counter to serve me anyway, so I skulked out.

What do rich people eat? Is it all truffles and foie gras and swan heads? Don't they ever get the urge for just, you know, a sandwich? Obviously I could have gone into one of the innumerable coffee shops and had a chef-prepared meal with a glass of pinot grigio, but I had places to go. I had walking to do. I didn't have time to sit down and mingle with the beautiful people. Disappointed and hungry, I headed north.

I should say that Whalley was absolutely charming, and if I was just on a day out, I'd have loved it. My empty stomach was doing my thinking for me.

The road out of the centre wound past hefty homes, discreetly hidden behind hedges and trees and video entryphones. On a tree in the front of one of the larger homes a battered sign demanded NO MORE HOMES FOR WHALLEY. It was a battle they'd clearly lost, because there were pocket developments springing up everywhere I looked. It got worse as I passed under the bypass and entered the neighbouring village of Barrow. It looked like a whole new town was being constructed there, concrete and bricks all over the place, heavy plant vehicles turning and churning up mud.

There was a shockingly ugly modern pub, made even worse by an infection of bling. A look through the big picture windows revealed garish interiors and animal prints. Behind it, a tiny cottage was being converted into something more befitting of the modern affluent resident, extended in every direction. It was a relief when I reached the village proper, and I found a down-to-earth community just getting on with the day.

Whalley's money hadn't reached this far, so there were still grey corporation houses and an abandoned Italian restaurant with metal shutters over the windows. Stubby remnants of snowmen melted in tiny front gardens.

I'd hoped there might be somewhere for me to get a snack here, but there wasn't so much as a Happy Shopper. The only food that seemed to be on sale was a farmhouse flogging free range eggs; its sign said You Can See Our Hens Wandering Freely Now Come And Try Their Eggs. That just sounds wrong, somehow. Also, I couldn't see a single chicken. There was a garden centre, looking forlorn in January and with an empty car park, and the low budget Southfork architecture of the Clitheroe Golf Club, and then I was on the main road with fields on either side.

I turned to singing as a way of distracting myself from the yawning pit that was my stomach. I had a crack at Writing's On The Wall, but there's no way I can hit those high notes like professional irritant and bloated ego monster Sam Smith (and now he's got an Oscar nomination! Unbearable!). I switched to something more in my register, where I didn't have to twist my testicles to get the end note, until I suddenly stopped in my tracks.

What an astonishing view. Just so beautiful. The play of light, the snow on the higher reaches. Fantastic.

Buoyed by the wonders of the landscape, I pushed on. Clitheroe announced itself in an almost as impressive manner, its castle keep puncturing the horizon and drawing me in.

The Whalley Road probably isn't Clitheroe's most glamorous gateway. There's an Aldi, and a stream of takeaways, and a record shop where I definitely detected a "herbal" scent, if you know what I mean. A pub was being converted into a block of flats, the swinging pub sign replaced by the developer's logo. A man jogged past me: his jersey had VEGAN RUNNERS written on it, so I deeply regretted not kicking him in the shins on the way for his smugness.

There were two shops with signs in the window bemoaning the quality of the rail service and calling for more stations. Chatburn is a village just to the north of Clitheroe and, to be honest, it's hard to understand why they haven't reopened it; as the slightly shouty poster above says, there's plenty of space and the track's in good condition.

Clitheroe town centre, meanwhile, was adorable. Affluent like Whalley, but larger, and unpretentious. There was a market, good shops, places to eat. The buildings were charming, the residents happy and content. No Greggs though; Clitheroe is a Steak Bake-free zone. They do have a Booths, built on former railway land. I went in for a nose, and came out with a packet of lemon mint Softmints, which are one of the best things I have ever put in my mouth.

The Softmints weren't enough to satiate my rampaging belly, though, so I headed to the Inn at the Station. I'm not sure why they've gone for that clunky name when "Station Hotel" is perfectly fine (and the frosted windows still bore that name, so it's a recent change). Inside, though, it was warm and charming and reasonably priced, so I ordered a club sandwich, not realising it was an absolute beast of a meal.

I still managed to eat it all though, because I am a fat bastard. I also had a couple of these:

Well, if you're going to break your healthy living, you may as well go the whole hog.

Thoroughly satiated, I wandered over the road to the railway station. The main building has been converted into a visitor centre and art gallery, but a newer building has been constructed behind with a staffed ticket office. As with much in Clitheroe, it's neat, pleasing, working.

The platform, meanwhile, was filled with teenagers heading back to the nearby towns after school. The train came in early and we boarded for a bit of warmth; again, why don't the trains carry on up the line? On a Sunday, there's a service over the Settle & Carlisle through Clitheroe - probably the only Sunday service in Britain that's actually better than the weekday schedule. Maybe I should write an angry poster and stick it in my window.

I'm sorry I took against the Clitheroe line. It turned out to be a great little route.

Monday, 11 January 2016

The Shock of the New

The last time I visited Wakefield, the blog post was titled The Worst Railway Station In Britain. I didn't think Wakefield Kirkgate was that bad - the title came from a Network Rail report. But the station had a definite air of dereliction and despair. It had been abandoned and neglected.

Not any more.

A huge amount of time, money and effort have been thrown at Kirkgate, and the result is a real transformation. Kirkgate's proud station building has been restored to something resembling its former glory. Bare walls have been scrubbed; canopies have been installed where there were previously nothing.

On the island platform, stranded between lines, they've made the station look respectable. When I visited in 2012, these windows weren't filled with glass - they were filled with corrugated plastic:

They've also built a proper cover for the underpass.

In the main building, new commercial spaces have been carved out; there's a cafe inside, and a taxi rank outside. There's grass and landscaping, and new artworks. What had been a dead hulk has been given new life.

The transformation's not as amazing as the one at Wakefield Westgate, though to be fair, they didn't do a restoration job there: they just demolished the old 1960s station and built a new one. I'd walked there from Kirkgate and had the usual rush of memories from the last time I was in the town centre - it was all very familiar. Then I turned a corner and entered a whole different place.

A huge area of land has been obliterated and colonised by hulks; big metallic shapes dropped randomly across the landscape by a deranged giant. It's like nothing else in Wakefield, a second division city in West Yorkshire. It's a bit of big league construction, and I don't feel like it fits.

The station, on the other hand, is a triumph. I'd complained last time that the old building was tired and grubby. Times have changed.

No, it's not innovative or avant-garde, but it is clean and practical. The interior is even better, changed from a narrow corridor with a flurry of facilities into a wide open space.

They've made room for more retail, of course, but it's been well-inserted. I was pleased to see familiar, trusted brands, too, rather than the usual overpriced railway station nonsense. A Subway sandwich beats an Upper Crust baguette any day.

The tilework is carried over onto the platforms; clean, practical, hard-wearing. Wakefield's two stations have gone from being an embarrassment to an example for the rest of the country.

The third part of my West Yorkshire Regeneration Tour was a return to Leeds station. I've always liked Leeds; it's bright and airy and works as a busy transport hub. It's well laid out and uncluttered. What lets it down is its interaction with the city. The main exit is onto a busy bus lane, with narrow pavements and steps to get you into the centre. Worse, it was lopsided, with an exit only to the north - if you wanted to get to the south of the city you had to walk all the way round the station, and, as one of the biggest stations outside London, that's a bit of a walk.

The disappointing front entrance is still a work in progress, but they've finally solved the problem of the southern exit.

It's taken them decades to right this wrong because of Leeds station's geography. The River Aire shadows the station, with a canalised branch running right under the tracks. A southern exit would have to overcome the geography. The architect's solution is a kind of pod, welded onto the back of the station and hovering right over the water.

I'm not sure about the gold - it's a bit gaudy for my tastes - but it certainly makes the entrance stand out. There are bridges across the water to take you to the new, slightly bland regeneration areas behind the station.

There's also an exit into the space beneath the arches, a space that's refusing to go trendy. It's dark and wet and a little intimidating, though I should imagine the new station exit will change that. Soon it'll be filled with artisan coffee stalls and trucks selling Mexican street food. For now, it's the location for a horrible murder in a Silent Witness.

I did a bit of a tour of the regeneration area behind the station. It feels underfed and empty, though as a district of restaurants and bars, a Tuesday afternoon probably isn't its prime. The best part is the canal basin, pretty and historic.

Inside the pod it's bright and airy. I'm not sure about the yellow - that will date very quickly - but I love the brick of the undercroft, exposed and cleaned.

The ride up to the main concourse is the best part of the whole station. Light streams in through the glass, though the lower windows have been frosted to stop tourists from standing there to admire the view and blocking the way for commuters.

Above you is a stunningly engineered curved roof. I was pleased I wasn't the only one taking pictures.

It's another wonderful facet to an already wonderful station. Can you sort out that main entrance, now?

Not any more.

A huge amount of time, money and effort have been thrown at Kirkgate, and the result is a real transformation. Kirkgate's proud station building has been restored to something resembling its former glory. Bare walls have been scrubbed; canopies have been installed where there were previously nothing.

On the island platform, stranded between lines, they've made the station look respectable. When I visited in 2012, these windows weren't filled with glass - they were filled with corrugated plastic:

They've also built a proper cover for the underpass.

In the main building, new commercial spaces have been carved out; there's a cafe inside, and a taxi rank outside. There's grass and landscaping, and new artworks. What had been a dead hulk has been given new life.

|

| In 2012... |

|

| ...and in 2016 |

A huge area of land has been obliterated and colonised by hulks; big metallic shapes dropped randomly across the landscape by a deranged giant. It's like nothing else in Wakefield, a second division city in West Yorkshire. It's a bit of big league construction, and I don't feel like it fits.

The station, on the other hand, is a triumph. I'd complained last time that the old building was tired and grubby. Times have changed.

|

| The old station entrance |

|

| The new station entrance |

No, it's not innovative or avant-garde, but it is clean and practical. The interior is even better, changed from a narrow corridor with a flurry of facilities into a wide open space.

They've made room for more retail, of course, but it's been well-inserted. I was pleased to see familiar, trusted brands, too, rather than the usual overpriced railway station nonsense. A Subway sandwich beats an Upper Crust baguette any day.

The tilework is carried over onto the platforms; clean, practical, hard-wearing. Wakefield's two stations have gone from being an embarrassment to an example for the rest of the country.

The third part of my West Yorkshire Regeneration Tour was a return to Leeds station. I've always liked Leeds; it's bright and airy and works as a busy transport hub. It's well laid out and uncluttered. What lets it down is its interaction with the city. The main exit is onto a busy bus lane, with narrow pavements and steps to get you into the centre. Worse, it was lopsided, with an exit only to the north - if you wanted to get to the south of the city you had to walk all the way round the station, and, as one of the biggest stations outside London, that's a bit of a walk.

The disappointing front entrance is still a work in progress, but they've finally solved the problem of the southern exit.

It's taken them decades to right this wrong because of Leeds station's geography. The River Aire shadows the station, with a canalised branch running right under the tracks. A southern exit would have to overcome the geography. The architect's solution is a kind of pod, welded onto the back of the station and hovering right over the water.

I'm not sure about the gold - it's a bit gaudy for my tastes - but it certainly makes the entrance stand out. There are bridges across the water to take you to the new, slightly bland regeneration areas behind the station.

There's also an exit into the space beneath the arches, a space that's refusing to go trendy. It's dark and wet and a little intimidating, though I should imagine the new station exit will change that. Soon it'll be filled with artisan coffee stalls and trucks selling Mexican street food. For now, it's the location for a horrible murder in a Silent Witness.

I did a bit of a tour of the regeneration area behind the station. It feels underfed and empty, though as a district of restaurants and bars, a Tuesday afternoon probably isn't its prime. The best part is the canal basin, pretty and historic.

Inside the pod it's bright and airy. I'm not sure about the yellow - that will date very quickly - but I love the brick of the undercroft, exposed and cleaned.

The ride up to the main concourse is the best part of the whole station. Light streams in through the glass, though the lower windows have been frosted to stop tourists from standing there to admire the view and blocking the way for commuters.

Above you is a stunningly engineered curved roof. I was pleased I wasn't the only one taking pictures.

It's another wonderful facet to an already wonderful station. Can you sort out that main entrance, now?