That isn't actually the moment. If I'd stopped to take a photo of my feet the minute I'd stepped off the train, I'd have caused quite a considerable blockade. Instead, I wandered off to a side part of the platform and took it.

Actually, now that I think about it, the line was on an embankment. So it wasn't really Lincolnshire soil at all. Not to mention the concrete of the platform.

In fact, probably best if you just ignore this whole intro.

The point I'm trying to make is that I'd never been to Lincolnshire before. In fact, the whole county was something of a mystery to me. It has a strange, nebulous presence in my mental geography, where it's "over there, somewhere". I knew it had Lincoln in it, of course, which has a cathedral, but beyond that: nothing. It was all new territory for me.

I was here to travel along a route which, on paper, seemed enormous.

According to the Northern Rail map, the route via Gainsborough and Brigg's the same length as the whole of South Yorkshire. As is often the way with railway diagrams, it's a bit misleading: that massive stretch of line between Brigg and Barnetby is actually less than five miles.

Three trains carried me across the Pennines to Gainsborough Lea Road station, to the south of the town. It was surrounded by trees, which made it doubly confusing when I stepped off the platform and looked down at the exit.

Was that some kind of climbing frame? A jungle treehouse I was expected to clamber down? No; the architects of Lea Road had just gone overboard with their design, putting little wooden roofs over the walkways, making it look less like a railway station and more like something you'd find in a pub garden to keep the kids quiet.

Tarzan's village was tucked behind a far more impressive station which was, regular readers will be unsurprised to learn, now derelict and abandoned. Its grand, symmetrical facade was falling to pieces, just a backdrop to short-term parking spaces.

I positioned myself in amongst the trees for the station sign...

...then felt an immediate pang of sadness. While the BR sign was all well and good, though in need of a clean, dumped in the grass verge was a much older relic. It was probably meant to be artfully positioned, but to my eyes, it looked abandoned and ignored.

I knew nothing about Gainsborough as a town. Nothing at all. My expectations were high though: I thought it would be classy, elegant, refined - the urban personification of this lady:

Perhaps there would be a smaller hat.

My walk into town convinced me this wasn't going to be the case. It wasn't that Gainsborough was especially bad, it had just clearly fallen on hard times. The recession seemed to have hit it harder than most. When your biggest factory has been turned into a half-filled retail park, it's not a great economic sign.

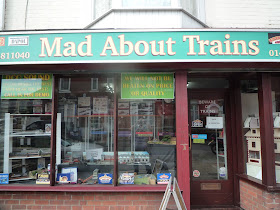

It wasn't all bad, retail wise. There was this place, for starters:

I thought "wow! I must have a poke round. I'll come back later." Then promptly forgot all about it.

The main portion of the town is based around a small triangular square. There was a market on, but it was all very half-hearted. I don't really 'get' markets. There was a time when they'd do the basics for a cheaper price - fruit and vegetables, and clothes, and maybe the odd bit of hardware. Now there's nothing there that you couldn't get in a supermarket or a pound shop, and at least there you're guaranteed some kind of recompense if things go wrong. Perhaps meat and fish, served by experts instead of the bored Saturday kids you get in Tesco, but for the rest of it - why bother?

I carried on down to the River Trent. The riverside walk has been regenerated, with interpretive artworks and clever paving and signs everywhere so that you never went a single moment without knowing exactly what you were looking at. The river is incredibly wide and deep here - Gainsborough was an important inland port for decades - and on a hot Saturday, the cool breeze across its surface was most welcome.

The Trent has a strong river bore, the Aegir, which sweeps along at the change of tide. The bore partly inspired George Eliot, who stayed in the town and used a thinly-veiled version of it in The Mill on the Floss; the flood at the end of the novel is a sort of Jerry Bruckheimer version of the Aegir. River bores are fascinating to watch - you can actually see the sheer weight of water driving along the channel, a massively powerful thrust that reminds you how we're just slaves to the planet.

I stared across the river for a little while, then carried on along the path. There were warehouses here, waiting to be turned into luxury flats, but with the occasional pocket of redevelopment. Most were shuttered up, but there was a retirement court in one, and a cafe tucked into the ground floor of another. I went inside and had a pot of tea and a slice of lemon drizzle cake for elevenses. Though the building was historic, the cafe had been decorated blandly, with the interesting brick walls plastered over and identikit furniture. The cake, however, was delicious, and I was able to squeeze three cups of tea out of the pot.

I headed into town across an empty car park, cut through a service yard, and ended up in what seemed to be the largest shop in town: the Lincolnshire Co-operative Department Store. It was delightful. I didn't even realise that the Co-op still had department stores, and judging by the interior of the shop, I'm not sure anyone else realises it's there either. It was all deliciously 1983. My nan worked in the Luton Co-op department store when I was very small, and this could have been the same one. The signage, decoration, even the stock - everything was preserved in aspic. The logo was still that incredibly dated curly sign that's been phased out everywhere else. I pictured Lincolnshire Co-op's high-ups telling head office where to shove their "good with food".

I took the glass lift up to the first floor, just because it was there, and also so I could pass the shiny, shiny mirrored balcony. I half expected Linda Evans to be waiting for me at the top, ready to throw some champagne in my face.

I know what you're thinking. "Fascinating though your attempts to recreate Joan Collins in Dynasty moments are, Scott, we don't come here for I Love the 80s recollections. We have Stuart Maconie for that. Where are the train stations?" And you have a point, impatient reader.

Thing is, I had to kill time. The Gainsborough to Barnetby line - as you may have guessed from its appearance on the map back there - doesn't have a very regular service. In fact, it barely gets a service at all. Every Saturday it gets three trains in each direction, and that's it. It means a wait of around four hours between each train.

I'd missed the earliest one, of course, travelling across the north, so I had to wander around until one o'clock. I was running out of things to look at though. Gainsborough's alright, but it's not exactly a throbbing metropolis. I found the parish church, which was very pretty, but also seemed to be in the middle of some kind of coffee morning. I didn't think my bladder could take more tea, and besides, I didn't want to be pigeonholed by the vicar and lectured about God, so I walked on.

In the end, I gave up. I decided I'd just sit on the platform for half an hour, so I went in search of the station. Which was harder than you'd think it would be. Clearly the town's worthies don't want to get people's hopes up about the services. If you advertise a "railway station", people might start expecting there to be trains, and that's a pretty rare occurrence. I ended up doing a circuit, which meant I got to see this billboard:

I don't think I've ever seen funeral options advertised on the side of a building before. It's a bit disconcerting. A little research reveals that it's a non-religious burial site, which sounds lovely, but which I found a bit disappointing. I mean, they still bury you. I thought they'd chuck you on a compost heap or something. Mulch you into the next existence. (Personally I want to be laid out in the desert and picked to death by vultures). It was another reminder that Lincolnshire is just a little bit odd.

Finally I found the station, hidden at the end of an overflow car park behind that retail park I saw earlier. One of the quietest urban stations in Britain.

I was surprised to find I wasn't alone. There was also a surveyor in an orange hi-vis vest under the footbridge, tapping away on his tablet PC and clutching one of those wheely-measuring devices under his arm. He wasn't Network Rail; his jacket had some other company's name on it, some sub-contractor who would theoretically save a load of money by introducing a whole new layer of complex bureaucracy to the procedure.

Even more shockingly, there were people in the platform shelter, forcing me to squat uncomfortably on the concrete. I regretted giving up on Gainsborough so quickly; now I had to spend half an hour leaning up against a chain-link fence, when I could have been having another slice of that lemon cake.

The surveyor wandered around, squinting intently at things. He kicked a couple of steps on the bridge, which doesn't strike me as the most scientific way to test their strength. Then he headed towards the shelter, no doubt to see if it was in need of repainting by scraping it off with a fingernail.

Big mistake.

While the line doesn't get much of a passenger service, freight trains are quite regular along it. It means that a certain kind of gentleman gravitates towards the station to watch them pass, and possibly note them down in a little book. These are the professional trainspotters; people who sneer at me and my pathetic attempts to remember the difference between a Pacer and a Sprinter.

The man in the shelter was hardcore and, on realising that the surveyor was a subcontractor, he launched into a lengthy monologue about the privatisation of the railways. This was a speech that he made without hesitation or deviation, that referred to acts of parliament by name and year, that dwelt upon Railtrack at length; this was an educative moment. It was also deeply uncomfortable to witness, as the polite, well-brought up surveyor squirmed and nodded and smiled and desperately tried to find a moment to step aside. He was probably in junior school when British Rail was broken up, but the trainspotter was, in some way, blaming him personally for the current state of the railways.

Beside him, her mind elsewhere, the man's wife took another bite of her sandwich. She didn't join in. She'd heard it all before. At least she was out of the house.

There was a gnat's breath of a pause in the rant and the surveyor took it. He practically ran across to the other platform, busying himself with something. Anything. I think he was probably just making a note of how many petals were on the daisies growing out of the concrete.

As I said: Lincolnshire's a bit odd.

I thought "wow! I must have a poke round. I'll come back later." Then promptly forgot all about it.

The main portion of the town is based around a small triangular square. There was a market on, but it was all very half-hearted. I don't really 'get' markets. There was a time when they'd do the basics for a cheaper price - fruit and vegetables, and clothes, and maybe the odd bit of hardware. Now there's nothing there that you couldn't get in a supermarket or a pound shop, and at least there you're guaranteed some kind of recompense if things go wrong. Perhaps meat and fish, served by experts instead of the bored Saturday kids you get in Tesco, but for the rest of it - why bother?

I carried on down to the River Trent. The riverside walk has been regenerated, with interpretive artworks and clever paving and signs everywhere so that you never went a single moment without knowing exactly what you were looking at. The river is incredibly wide and deep here - Gainsborough was an important inland port for decades - and on a hot Saturday, the cool breeze across its surface was most welcome.

The Trent has a strong river bore, the Aegir, which sweeps along at the change of tide. The bore partly inspired George Eliot, who stayed in the town and used a thinly-veiled version of it in The Mill on the Floss; the flood at the end of the novel is a sort of Jerry Bruckheimer version of the Aegir. River bores are fascinating to watch - you can actually see the sheer weight of water driving along the channel, a massively powerful thrust that reminds you how we're just slaves to the planet.

I stared across the river for a little while, then carried on along the path. There were warehouses here, waiting to be turned into luxury flats, but with the occasional pocket of redevelopment. Most were shuttered up, but there was a retirement court in one, and a cafe tucked into the ground floor of another. I went inside and had a pot of tea and a slice of lemon drizzle cake for elevenses. Though the building was historic, the cafe had been decorated blandly, with the interesting brick walls plastered over and identikit furniture. The cake, however, was delicious, and I was able to squeeze three cups of tea out of the pot.

I headed into town across an empty car park, cut through a service yard, and ended up in what seemed to be the largest shop in town: the Lincolnshire Co-operative Department Store. It was delightful. I didn't even realise that the Co-op still had department stores, and judging by the interior of the shop, I'm not sure anyone else realises it's there either. It was all deliciously 1983. My nan worked in the Luton Co-op department store when I was very small, and this could have been the same one. The signage, decoration, even the stock - everything was preserved in aspic. The logo was still that incredibly dated curly sign that's been phased out everywhere else. I pictured Lincolnshire Co-op's high-ups telling head office where to shove their "good with food".

I took the glass lift up to the first floor, just because it was there, and also so I could pass the shiny, shiny mirrored balcony. I half expected Linda Evans to be waiting for me at the top, ready to throw some champagne in my face.

I know what you're thinking. "Fascinating though your attempts to recreate Joan Collins in Dynasty moments are, Scott, we don't come here for I Love the 80s recollections. We have Stuart Maconie for that. Where are the train stations?" And you have a point, impatient reader.

Thing is, I had to kill time. The Gainsborough to Barnetby line - as you may have guessed from its appearance on the map back there - doesn't have a very regular service. In fact, it barely gets a service at all. Every Saturday it gets three trains in each direction, and that's it. It means a wait of around four hours between each train.

I'd missed the earliest one, of course, travelling across the north, so I had to wander around until one o'clock. I was running out of things to look at though. Gainsborough's alright, but it's not exactly a throbbing metropolis. I found the parish church, which was very pretty, but also seemed to be in the middle of some kind of coffee morning. I didn't think my bladder could take more tea, and besides, I didn't want to be pigeonholed by the vicar and lectured about God, so I walked on.

In the end, I gave up. I decided I'd just sit on the platform for half an hour, so I went in search of the station. Which was harder than you'd think it would be. Clearly the town's worthies don't want to get people's hopes up about the services. If you advertise a "railway station", people might start expecting there to be trains, and that's a pretty rare occurrence. I ended up doing a circuit, which meant I got to see this billboard:

I don't think I've ever seen funeral options advertised on the side of a building before. It's a bit disconcerting. A little research reveals that it's a non-religious burial site, which sounds lovely, but which I found a bit disappointing. I mean, they still bury you. I thought they'd chuck you on a compost heap or something. Mulch you into the next existence. (Personally I want to be laid out in the desert and picked to death by vultures). It was another reminder that Lincolnshire is just a little bit odd.

Finally I found the station, hidden at the end of an overflow car park behind that retail park I saw earlier. One of the quietest urban stations in Britain.

I was surprised to find I wasn't alone. There was also a surveyor in an orange hi-vis vest under the footbridge, tapping away on his tablet PC and clutching one of those wheely-measuring devices under his arm. He wasn't Network Rail; his jacket had some other company's name on it, some sub-contractor who would theoretically save a load of money by introducing a whole new layer of complex bureaucracy to the procedure.

Even more shockingly, there were people in the platform shelter, forcing me to squat uncomfortably on the concrete. I regretted giving up on Gainsborough so quickly; now I had to spend half an hour leaning up against a chain-link fence, when I could have been having another slice of that lemon cake.

The surveyor wandered around, squinting intently at things. He kicked a couple of steps on the bridge, which doesn't strike me as the most scientific way to test their strength. Then he headed towards the shelter, no doubt to see if it was in need of repainting by scraping it off with a fingernail.

Big mistake.

While the line doesn't get much of a passenger service, freight trains are quite regular along it. It means that a certain kind of gentleman gravitates towards the station to watch them pass, and possibly note them down in a little book. These are the professional trainspotters; people who sneer at me and my pathetic attempts to remember the difference between a Pacer and a Sprinter.

The man in the shelter was hardcore and, on realising that the surveyor was a subcontractor, he launched into a lengthy monologue about the privatisation of the railways. This was a speech that he made without hesitation or deviation, that referred to acts of parliament by name and year, that dwelt upon Railtrack at length; this was an educative moment. It was also deeply uncomfortable to witness, as the polite, well-brought up surveyor squirmed and nodded and smiled and desperately tried to find a moment to step aside. He was probably in junior school when British Rail was broken up, but the trainspotter was, in some way, blaming him personally for the current state of the railways.

Beside him, her mind elsewhere, the man's wife took another bite of her sandwich. She didn't join in. She'd heard it all before. At least she was out of the house.

There was a gnat's breath of a pause in the rant and the surveyor took it. He practically ran across to the other platform, busying himself with something. Anything. I think he was probably just making a note of how many petals were on the daisies growing out of the concrete.

As I said: Lincolnshire's a bit odd.

Just discovered your blog via a comment you left on Diamond Geezer's blog... A good read!

ReplyDeleteCheers, EskimoPie

That's good of you to say! Thanks :)

ReplyDeleteFirst time you've ever set foot in Lincolnshire? It's my favourite county! Been going every year since I was born!

ReplyDeleteThis needs to be updated

ReplyDelete